Noise in Music

There is a school of thought in regards to musical intervals and timbres which believes that there is no absolute truth or beauty in music, and that musical enjoyment is only based on the preferences of the individual listener.

One of the main arguments for musical relativism is the argument that music is not "noise", even extreme metal or experimental music, and that the intent as art is a sufficient cause for something to be appreciated as music. The result of this is that "music" can become so abstracted from the typical definition that typical noises heard in daily life, such a a rhythmic cooler humming or a loose car part that make a semi-predictable tapping sound, might end up on the threshold of "music" if they were performed in front of a live audience.

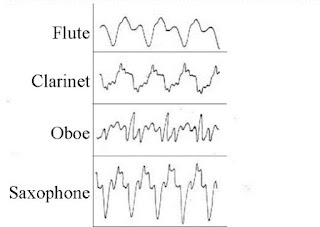

My defense of the similarity of some music to noise should be somewhat clear by itself, but here is a picture of the waveforms of four different instruments:

The flute's waveform is the closest to a sine wave, which is the purest type of sound.

For comparison, here is white noise, the purest form of noise:

It is clear that the oboe and especially the saxophone have more noise in them than the flute and clarinet do.

Noise has many uses in music. It can be mixed into a song at extremely low levels to make it more natural, it's a feature of some acoustic instruments such as drums and saxophones, and it is used much more obviously in effects for electric guitars and other instruments.

In the same way that different instruments have a varying amount of noise, musical intervals also vary in the same manner. An octave is represented by the ratio 1/2, and it's the simplest duophonic interval. A minor second, on the other hand, is 15/16. This interval will always produce a noisier sound than an octave.

The history of Western music has primarily involved an increasing amount of noise. Although it's difficult to tell how noisy music was many thousands of years ago, it hit a minimum of noise during the plainsong era. Of course, folk music at that time did not follow the same rules, but church plainsong not not use any intervals at all except possibly octaves.

Anti-noise intervallic rules were kept in place, more or less, until Bach started to experiment with dissonance. In the Romantic era, little was forbid, and noise flourished even more with the advent of the electric guitar and experimental art music. Luigi Russolo was an early noise music artist in the beginning of the 20th century.

The book Meta-Hodos states that the parameters of music have widened considerably in recent years, as far as more noise being permissible, more dynamic levels, and almost any other characteristic. Now, it is not clear exactly what music is, with conservatives holding out that noise is not music but a large contingency of others listening to genres which contain large proportions of noise.

Even though defining music may be getting increasingly difficult, with the easy access to it and huge variety of it that we have now, enjoying it is easier than it ever has been.

Perhaps it's possible to listen to Handel and Slipknot right after each other!

One of the main arguments for musical relativism is the argument that music is not "noise", even extreme metal or experimental music, and that the intent as art is a sufficient cause for something to be appreciated as music. The result of this is that "music" can become so abstracted from the typical definition that typical noises heard in daily life, such a a rhythmic cooler humming or a loose car part that make a semi-predictable tapping sound, might end up on the threshold of "music" if they were performed in front of a live audience.

My defense of the similarity of some music to noise should be somewhat clear by itself, but here is a picture of the waveforms of four different instruments:

The flute's waveform is the closest to a sine wave, which is the purest type of sound.

For comparison, here is white noise, the purest form of noise:

It is clear that the oboe and especially the saxophone have more noise in them than the flute and clarinet do.

Noise has many uses in music. It can be mixed into a song at extremely low levels to make it more natural, it's a feature of some acoustic instruments such as drums and saxophones, and it is used much more obviously in effects for electric guitars and other instruments.

In the same way that different instruments have a varying amount of noise, musical intervals also vary in the same manner. An octave is represented by the ratio 1/2, and it's the simplest duophonic interval. A minor second, on the other hand, is 15/16. This interval will always produce a noisier sound than an octave.

The history of Western music has primarily involved an increasing amount of noise. Although it's difficult to tell how noisy music was many thousands of years ago, it hit a minimum of noise during the plainsong era. Of course, folk music at that time did not follow the same rules, but church plainsong not not use any intervals at all except possibly octaves.

Anti-noise intervallic rules were kept in place, more or less, until Bach started to experiment with dissonance. In the Romantic era, little was forbid, and noise flourished even more with the advent of the electric guitar and experimental art music. Luigi Russolo was an early noise music artist in the beginning of the 20th century.

The book Meta-Hodos states that the parameters of music have widened considerably in recent years, as far as more noise being permissible, more dynamic levels, and almost any other characteristic. Now, it is not clear exactly what music is, with conservatives holding out that noise is not music but a large contingency of others listening to genres which contain large proportions of noise.

Even though defining music may be getting increasingly difficult, with the easy access to it and huge variety of it that we have now, enjoying it is easier than it ever has been.

Perhaps it's possible to listen to Handel and Slipknot right after each other!

Comments

Post a Comment